Before America emerged as a modern global power, the history of the United States began in Europe before the New World was known, and in America before the arrival of the European settlers. The old continent, during the time of the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus (1451- 1506), entered a new era of "expansion and exploration of the world" but in a purely European way, reaching distant horizons they had not seen before.

Between Two Worlds

The hopes that the European settler groups brought from the "Old World" to the "New World" were as varied as their nations and peoples, ranging from greed for gold or the love of adventure, the quest for glory or the honor of serving the ruler or escaping from his oppression and injustice, or seeking religious freedom and worship, or escaping from poverty, famines, and prisons, or establishing the farm of dreams.

Some came or were brought without dreams, used as serfs in tobacco, cotton, and sugarcane plantations or as slaves in mines, mills, and railroad projects spanning from ocean to ocean. For nearly two centuries, life on the new continent melded them into a single crucible to form the American people.

For the European settlers, success and the formation of empires necessarily meant for the natives (the Red Indian kingdoms) a prolonged and losing bloody battle for survival, existence, and the preservation of their land, life, and livelihoods.

The colonies were dominated by elites who reflected economic interests and religious concerns beneath the colonization projects, ranging from Puritan (Congregational) ministers and wealthy landowners to investment and trading companies (from the English mercantile class), some adventurers, and a few intellectuals who had received higher education at the time.

Contrary to their original desire to migrate to the James Town colony in Virginia, the "Pilgrims," a religious English immigrant group due to sea storms that led to the stranding of their ship Mayflower, were forced to land in New England, northeast America. They founded the Plymouth city, now in the state of Massachusetts. The London Puritans had established the New Haven colony, currently in the state of Connecticut, initially inhabited and settled by Puritans only.

The Puritans' presence strengthened on the coast of Massachusetts after the arrival of many groups. They objected to the Anglican Church (British) without thinking of separating from it; instead, they wanted to "purify" it. These groups swiftly succeeded due to their organization, which made them grow rapidly, especially after the "Great Migration" that brought about 25,000 of them to Massachusetts, fleeing persecution by the Anglican Church during the reign of King Charles I.

When these Puritans took control of the Massachusetts government, they did not accept any opposition, forcing dissenters to leave Boston several times, leading to the establishment of several new settlements, and later states: Rhode Island, Vermont, Maine.

Sociocultural Formation of the Settlers

The main demographic block of the immigrants and settlers was purely Protestant. Even when the British allowed non-British immigration to the New World colonies, it was confined to three groups: Palatine Germans, Scots-Irish, and Black slaves.

German migration began after 1710 following the British Parliament's approval to grant citizenship to every Protestant who migrated to America. The German emigrants left their homeland fleeing poverty, conflicts, and religious persecution, settling inland away from the coasts, especially in Pennsylvania with its vast land, becoming known as the Pennsylvania Dutch. They were followed by Presbyterian (Protestant Church) migrants from Northern Scotland and Ireland fleeing persecution by the Anglican Church in Scotland and the Catholic Church in Ireland, and an increase in population surplus versus limited economic resources which sometimes caused famines.

Groups of French "Huguenots" (Protestants), who suffered persecution to the point of massacres late in the 18th and early 19th centuries, also migrated. It's said that the number of victims of these massacres approached a million, a massive human and moral loss for France, considering the cultural, educational, and intellectual distinction these Huguenots represented. Additionally, Swiss and Swedish groups settled initially in the (state of) Delaware Valley, representing a small addition to the settlement configuration.

The Germans preceded others in settling the mountainous regions in Virginia, North and South Carolina, and Pennsylvania. Then, the Scots-Irish settled in the west and southwest, while the Huguenots also settled in Carolina, the Scots in Carolina and Georgia, and the Dutch in New York.

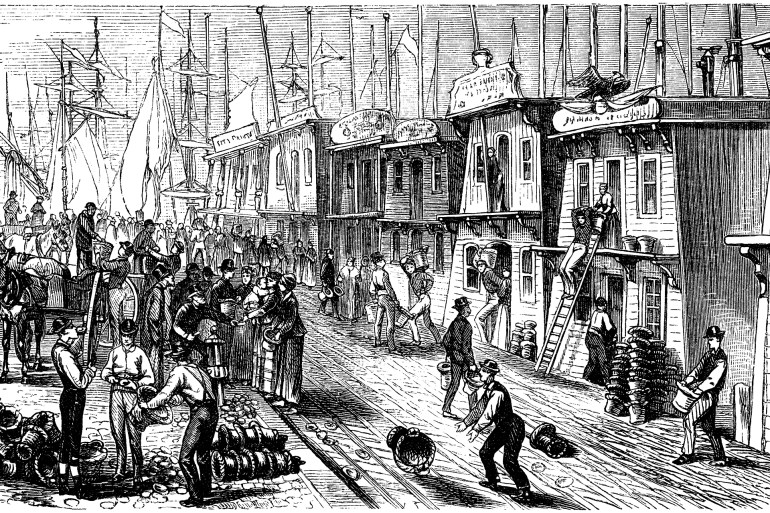

Oyster harbor in New York (Shutterstock)

Most of these immigrant groups, with their different cultures, lost much of their characteristics, traditions, and original identity upon integrating into the "settlement" society, with some exceptions. Perhaps the Amish Protestant sect of German-Dutch origin is the most prominent. They still uphold many of their ethics, traditions, and original lifestyles as they brought them from Europe in the 18th century, with the majority living in Pennsylvania and some in Indiana.

Although the European immigrants came burdened with their social heritage and sectarian and class burdens and the existing disparities among them in wealth and power, these class and social inequalities among them noticeably shrunk, much less extensively and severely than in their original European homelands.

The new aristocracy in America was made up of senior officials, clergymen, artisans, large ship owners, traders, and British feudal lords. The abundance of natural economic resources led to improved social conditions and living standards in American society.

However, there was a distinction between the upper-class of British-descended colonial officers and the rising new strata that improved their socioeconomic conditions due to available opportunities and resource abundance.

On the other hand, the middle class comprised farmers, traders, and technicians, representing the vast majority of the colonial population. The third class consisted of non-craft free labor. The term "free labor" is essential here to distinguish them from the fourth-class group, mainly contract service workers who committed to working for several years, typically between three and seven, in exchange for being brought from Europe to America, alongside the fourth-class African slaves.

Religious Life in the Colonies

Religion played a crucially important role in the life, thought, and worldview of the colonial population at that time. The "settlement" demographic then included numerous groups of marginal Protestants – those not affiliated with the leading main Protestant churches like Anglican and who did not consider them a reference but instead preferred to form their religious communities, along with their rituals and devotions they chose to adhere to.

These groups had been subjected to persecution by the official churches in Europe, which drove them to migrate to America, where they found safe haven, thrived, and spread their churches, becoming a hallmark of life, socializing, and thinking in the New World. While it's true to say that the diversity and variety of the religious backgrounds of the migration and settlement groups in America created an atmosphere of religious tolerance more than anywhere else in Europe, it's also true that this experience witnessed early persecution by some churches and religious groups against other Christian churches and groups. In the 17th century, an individual was sentenced to death in Pennsylvania merely for belonging to the "Quakers" Christian sect, and it took a long time before these unfair sentences and laws were repealed.

The beliefs and practices of the Puritan sect in New England had a greater impact on life in the new settlement society than any other religious group, as the Puritans were followers of the great Protestant reformer John Calvin, who believed that humans are guided, not free, and that God has already chosen those whom he will save in the afterlife, which spurred many Puritans towards "mysticism" in search of knowing if they were among the chosen by God, as well as focusing on improving their conditions and others'. The Puritans adhered to a strict moral code; they issued laws prohibiting work on Sundays and mandating community church attendance.

Early settlers in North America (Shutterstock)

Despite seeking religious freedom in the New World to escape religious persecution in Europe, and actually enjoying it, they persecuted other religious sects such as Baptists, Quakers, Jews, Catholics, and others.

With the prevalent belief in religious (magic) and the curse of witches in Europe and America in the 17th century, the Puritans in 1692 were involved in witch hunts and trials, which resulted in 19 executions before stopping the pursuit series, which brought prominent figures to trial, leading to the loss of faith in some Puritan leaders.

The church organization of the Puritan sect was independent or "congregational," meaning they believed in the freedom of each church from any external control or dominance. This principle applied to most Protestant churches that emerged and spread in the New World, a genuine and historical Protestant tradition that began with the rejection of the Catholic Church's control as the "universal" or God's one church and repository of sacred mysteries. This principle was applied gradually to also reject the Anglican Church's dominance over Protestant sects.

In Rhode Island, the most prominent religious sect was Baptist, which began its presence there led by the educated Cambridge University graduate, minister Roger Williams, who had previously called for purchasing land from Indian tribes instead of seizing it, objected to the Puritans' practices in Boston, and was expelled along with his followers. The Quaker sect also had a notable presence in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, and the Scots-Irish immigrants brought groups of Lutherans, Mennonites, and Moravians. Many Puritans settled in New Jersey. Groups of Dutch and German Reformers settled in New York, which did not have a prominent religious character.

In the southern colonies, Anglican church groups had a significant presence, while Catholics were the most noticeable group in Maryland, particularly Baltimore city with a Catholic bishop and long political institutional dominance by Catholics. The presence of Anglicans, with their openness to life and social ease in the south, distinguished it from the north, which was colored with a somber hue by the Puritans and experienced religious extremism. The Presbyterians (followers of the Presbyterian Church), Baptists, and Quakers settled in the inner southern regions.

Major Issues

In light of the characteristics of the early American "settlement" formation, it is possible to diagnose the core issues and primary concerns or the major matters representing the heart of this extended colonial historical experience, which have defined, and still define, the general outlines shared among political and ideological ideas and lineages in American history, as well as the differences and variations among them.

These issues reveal the formation pathways of the United States and its current direction. These concerns can be succinctly summarized into several matters:

First: Escaping poverty, unemployment, and famines suffered by European societies that drove out immigrants, and reaching the new promised land, the land of milk and honey, as they were inspired by or embodied texts from the Torah (Old Testament) where the land stretched endlessly from ocean to ocean, boundless natural resources, immense wealth and abundance, freedom of trade, capitalist economy, and perpetual progress and prosperity.

Second: Liberation from the tyranny and autocracy of kings and rulers in Europe, who governed in an absolute autocratic manner, and the groups' aspiration to a significant degree of self-independence, popular representation, and managing their affairs themselves.

Americans in New York during the Civil War (Shutterstock)

Third: Religious freedom and escape from persecution and dominance of the main official churches (Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran), and the formation of independent religious communities, with their convictions, traditions, rituals, and cosmic vision.

Fourth: The elite's aspiration to achieve glory, power, and fame in the New World and build their new imperial projects liberated from the control of traditional European kingdoms and empires, cutting off their hand from interfering in the New World affairs and imperial expansion at the expense of earlier imperial projects: Spanish, British, French, Portuguese, and Dutch.

Fifth: Belief in the uniqueness of the American experience, the particularity of the American Revolution in civilization, human and religious history, and the distinction of the American Republic in its political, rights, and economic organization compared to the rest of the Old World, and its leadership in the space of human progress. Thus, a sense of exceptionality, superiority, and the notion that America is a nation with a special mission, intertwining religion with American literature and nationalism, thus establishing what is called "civil religion" in America.

This language not only borrows from the Gospels of the New Testament but also from the Old Testament. The early migrants likening Europe to Pharaonic Egypt as in the Old Testament, and compare the United States to the "Promised Land."

Sixth: The American Revolution's wars against the British entrenched the people's right to bear arms, the formation of armed militias, adherence to the principle of self-security, and legally established individual sovereignty within their lands or properties.

These lines have been – and still are – the general determinants shaping American political thought among elites and the masses. Ideologies and American political lineages have been formed based on positions taken towards them.